Andreas Albrectsen

Andreas Albrectsen (f.1986, bor och arbetar i Köpenhamn.) Han tog sin masterexamen på Malmö Konsthögskola 2013. Samma år fick han motta Edstranska Stiftelsens stipendium, samt på nytt 2019. Hans teckningar baseras på fria associationer till de olika bilder han utgår ifrån, antingen fotografier som han samlat på sig, eller bilder han hittat på internet eller i gamla publikationer. Han är intresserad av premisserna för internet; att all information finns tillgänglig samtidigt, vilket gör att tidsperspektiv och historiska händelseförlopp sudddas ut. Papprets tomrum som omsluter hans teckningar är en hänvisning till detta, det flyktiga utrymmet där vi delar vår kunskap och okunnighet. Han arbetar med klassiska material som kol och blyerts.

Andreas Albrectsen (DK/BR) har studerat vid Gerrit Rietveld Academie, Amsterdam och Konsthögskolan i Malmö. Senaste utställningar: Fotografisk Center Copenhagen, Galeria Anita Schwartz Rio de Janeiro, Market Debut Stockholm (C.C.C), Nils Stærk, Haus N Athens, Minuseins Vienna, SMK - Statens Museum For Kunst. Albrectsen har tidigare visats på Malmö Konsthall, Skissernas Museum, Vejle Kunstmuseum, ARoS Art Museum, BOZAR - Centre of Fine Arts, Bruxelles, Maison Descartes Amsterdam, Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Parts Project, The Hague. Hans verk finns i samlingar på The National Musem of Fine Arts of Brazil, SMK - The National Gallery of Denmark, Malmö Art Museum, the New Carlsberg Foundation, The Danish Arts Foundation och Region Skåne.

Text by Andreas Albrectsen

In April 2019 I travelled to Paranapiacaba, located in the midst of the 'Serra do Mar' forest, 61 km southeast from Sao Paulo. Paranapiacaba was built as a railway village in the mid-1800s by the British. Here, they established an industrial district in a panoptical design - constructed in a Victorian-style with a clock tower resembling Big Ben. Paranapiacaba was founded on top of original native-Indian pathways through the forest. Its name originally derives from the Tupi-Indian language and can be translated to: "A place to watch the sea".

The village and its railway route were decommissioned by the Brazilian authorities during the 1970s. Now it stands as a memorial site to an era of transatlantic trade and industry. The rainforest surrounding Paranapiacaba has taken its toll on the village. The original 19th-century wooden houses and abandoned steam engine locomotives imported by the British has gradually been deteriorating if not entirely consumed by the wild nature.

When I first arrived at Paranapiacaba back in April, I found myself entering the village and carefully blind walking through the small panoptic brick roads. An impenetrable mist descended from the nearby mountains had covered the terrain. While my visibility was close to gone, I decided to photograph whatever was in front of me as I instinctively walked through the village towards my destination. With my camera, a 1981 Contax, I managed to document parts of the abandoned train material, 19th-century houses and Victorian street lamps as I passed along.

My initial idea with the trip was to photograph the deteriorating railway tracks and using the developed negative film as the basis of a series of works. I saw the iconic similarity between the filmstrip and train tracks, deciding that this would constitute the visual framework of this new series. The film reel is a vessel for a narrative course, while the negatives are 'latent' images. As an object, the film reel simultaneously displays and veils its content and the contradiction of this characteristic interested me. Merging images of railway-ruins with the ambiguous aesthetical quality of the negative was conceptually clear to me. Photographs are themselves ruins because they are a reminder of the future when our own present becomes history.

"It is not a question of preserving the past, but of redeeming vanished hopes" - this sentence by Horkheimer/Adorno which was also used as an exhibition title by the late Raffael Rheinsberg resonated within me during a late-night conversation with my Brazilian host Dona Zelia back in Paranapiacaba. She expressed her sadness over the election of President Jair Bolsonaro and his hostile position towards the native-Indian population. We also discussed the president's nostalgic glorification of the former military dictatorship. "Brazil does not have a future because it does not want to have a past", she finally concluded. Dona Zelias statement stayed me for the duration of my trip. "Nostalgia... is essentially history without guilt", Michael Kammen once wrote - I suppose that this was what she meant with the country suppressing its collective memory.

The mountain-mist kept veiling the village for hours every day during my visit. In the developed filmstrips from Paranapiacaba, the white vapour only seems to corroborate the transitoriness of the motif in the film negative. While looking at them in the studio, it became clear that it was the film reel as a vessel that I needed to work with - not the individual images. I discovered that by laying a transparent drafting film over the negatives, taping its edges carefully and pressing a block of raw graphite over the drafting film and underlying filmstrips, I could make a physical imprint of the entire thing.

''Frottage' - which derives from the french word for 'rubbing' - is a manual developing method to reveal hidden structures in a surface. This method is commonly used by archaeologists to document ancient petroglyphs in 1:1 when a photograph does not suffice. Max Ernst, the surrealist who is widely credited to invent the frottage-technique within the arts, is quoted saying: "This is a forest, everything I make automatically comes out of forests" when interviewed about his anthology of frottage drawings 'Histoire Naturelle'. Ernst was drawn to the hallucinatory auto-figuration that the technique provided him.

The frottage-series I made from Paranapiacaba also derives from nature, i.e. the coastal forests of 'Serra do Mar' where the undeveloped film rolls travelled from. But my strategy never relied on the accidental figuration of the frottage. My main focus was to register the repetitive perforations in the filmstrip as its surface is plane and smooth. With the idea in mind of the negative as a 'latent' image, the metallic black graphite with all its inconsistencies in pressure created an abstract visual progression throughout the drawing. While the works are easily recognized for its photographic characteristic, they do not reveal anything. They are physical traces of potential images, documents of a personal journey into a collective history. In final, I will end this text with a quote by Roland Barthes from his book Camera Lucida:

" Not only is the photograph never, in essence, a memory. But it actually blocks memory, quickly becomes a counter-memory (...) The photograph is violent: not because it shows violent things, but because on each occasion it fills the sight by force, and because in it nothing can be refused or transformed".

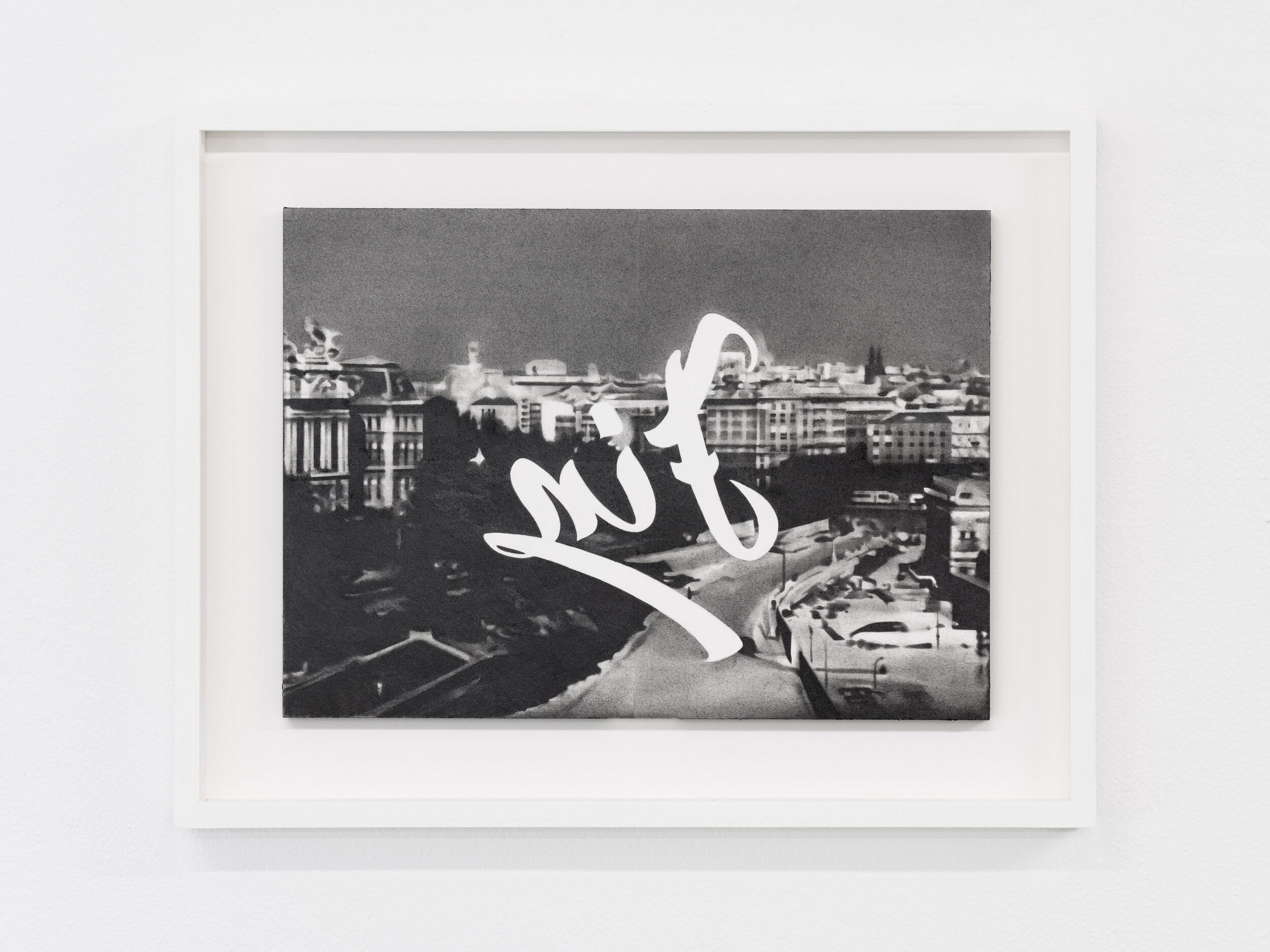

installationsbild 2020

detaljbild